Going Against the Grain: All About Salmon Spawning

It might not seem important to think about salmon and muse over their history or ponder what their life is like today. But it’s a vital story in the scheme of our ecological environment and what is happening to a once extremely valuable species. Besides, salmon is the best example of the cog in the wheel of how a fish species figure into the mystery of migration.

Historical Fish Stories

Salmon was a food preference even among peoples of the Paleolithic era—called the old stone age of about two and a half million years ago during a time when people chipped rudimentary stone tools. Salmon was also a staple during the Plinian period, which was marked by volcanic eruptions, such that destroyed Roman cities. Basically salmon was a food source around the world for thousands of years.

Archeological digs have found French caves common to 300 BC wherein a full-sized salmon relief is carved into stone. These Celtic tribes even developed a kind of lore or mystery saying that salmon were: “the keepers of wisdom.” The people of the time honored salmon for their brave witness against predators, for how they effortlessly traveled through the air to return back to their place of birth—and feelings about their prowess went so deep, that it was thought a person could gain sacred knowledge by just touching a salmon.

Disrespecting the Salmon

And then there were too many instances of crisis for salmon. What was often referred to as a “political paralysis” over various periods of time of salmon exploitation, certain debacles meant that: salmon were overfished, over canned, plundered for money, cordoned off from their streams and spawning areas, and nearly rendered extinct.

Even Charles Dickens wrote about his fear of extinction of salmon in his magazine, All The Year Round, published in 1861, “The cry of ‘Salmon in Danger!’ is now resounding throughout the length and breadth of the land.”

In his book, Treasures of the Deep, Daniel B. Fearing wrote: In making comparisons between the supplies of fish and other flesh, we must also recollect that fish, or at least salmon, though higher in money value, cost nothing for their “keep”, make bare no pastures, hollow out no turnips, consume no corn but are, as Franklin expressed it, “bits of silver pulled out of the water”.

Fishing Frenzy, Pollution, Logging, Urbanization, and Dams

In the history of the United States, when the railroad reached Santa Cruz in 1876, the popularity of fishing was out of control. It was the river as much as the beach that drew tourists and exploiters. Santa Cruz promoted itself as a sportsman’s paradise and the business boom at the start of the season was like a gold rush. Due to nonregulation, fish were taken by hook, nets, pitchforks and even dynamite. Salmon were thought of as inexhaustible.

New methods of food preservation were a huge blow to populations of salmon. The Industrial Revolution created factories, canning, pollution, sewage and rampant poaching. In England, there were so many Parliamentary bills throughout the 1500 to 1800s for salmon, but the lack of enforcement created extinctions in Scottish, French, and English rivers.

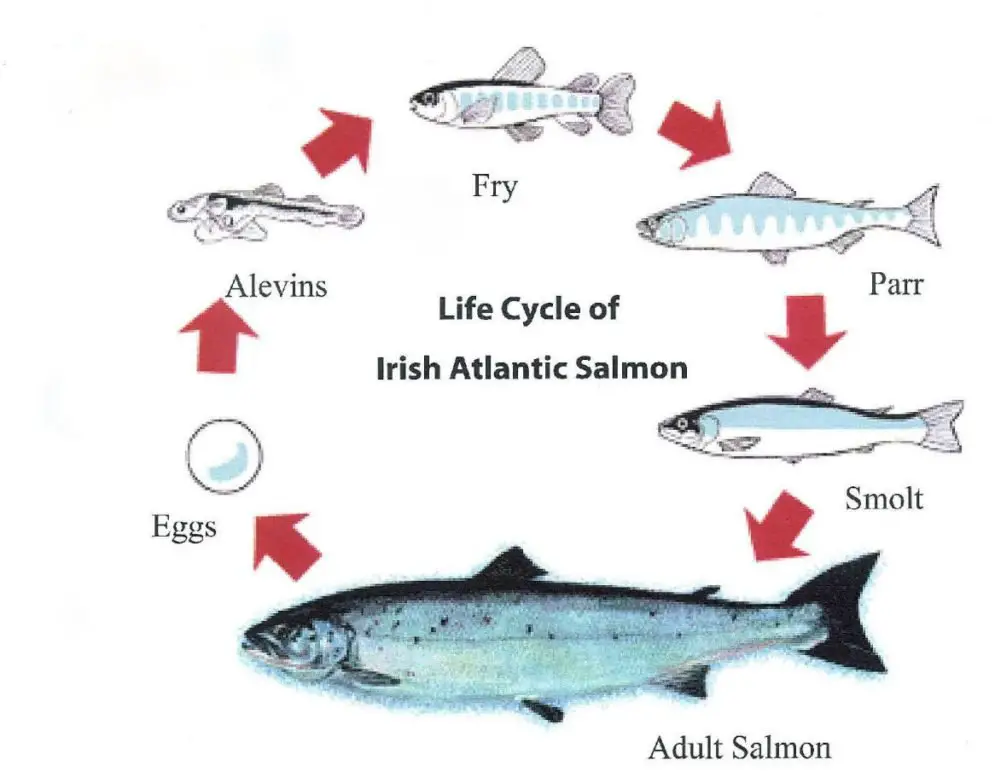

Basic Salmon Life Cycle

Though it varies among the five species of Pacific salmon, in its simplest form: it is hatch, migrate, spawn, and die. The varieties here are: King or Chinook salmon, Chum or Calico salmon (Keta), Coho salmon, Sockeye, and Pink (Humpback) salmon. There is only one species in the Atlantic, aptly named the Atlantic salmon, and is generally farm raised and now coming from Canada, Chile, and Norway. The term salmon refers to a variety of species that are all “anadromous” fish, which means they are born in freshwater rivers and streams. Steelhead trout is also added to the salmon family, while they spend most of their time in the ocean but will often spawn several times before they die, unlike the other salmon species.

When salmon migrate, they change colors; in the ocean they are typically silver and can turn red on their return to rivers. They breathe through gills and can range from the largest, up to 80 pounds (10 kg), to the smallest, between three and six pounds (1-3 kg).

How They Migrate

Most salmon migrate just two times in their lives. First, they travel from the freshwater streams high in the hills or mountains where they were spawned to the ocean. Then, as adults, they migrate back to their natal streams to have babies. Their journey can be hundreds or thousands of miles. The west coast trip may take them out as far as Alaska or surprisingly, even Japan.

They return to streams and rivers to ultimately reproduce and, typically between September and November. The migratory strategy of reproducing in freshwater, yet feeding primarily in marine waters, is known as anadromy. There have been theories about the urge to spawn because swimming upstream is a proven positive for reproductive survival and the rocky conditions are most beneficial to laying eggs.

In recent years, studies have shown that in the open ocean environment, salmon use the magnetic field of the Earth to guide their migration. This helps them move from the coastal areas near their spawning grounds to rich feeding areas, and then back again toward the end of their lives. Experts in migration feel the ability to travel this way has a genetic component that is inherited. It is postulated that young salmon can even remember the smell of their home stream and that they memorize the smells all the way to the path of the open ocean. They are using two comma-shaped holes on either side of their heads called olfactory receptors. Can they make a wrong turn? Of course, but something does point them back and researchers again believe it is the smell that guides them.

Dangers in Travel

Salmon are powerful swimmers and they fight their way against strong currents, rapids, waterfalls and even dams. Salmon can jump about 2 meters or more, higher. You can be sure that bears, eagles, otters and raccoons are there to grasp them out of the air. And salmon also face variable temperatures, disease, different salinities (salt content), pollution, and physical barriers because of habit alteration.

Fish that can live in both fresh and salt water are: Anadromous (ah NAD ruh mus). In the United States though, more than 2 million dams and other barriers block fish from migrating upstream. Blocked access to spawning grounds and habitat degradation caused by dams and culverts is a major problem for salmon. As a result, many fish populations have declined. Atlantic salmon are restricted from being fished in the United States and are considered an endangered species.

In the past, humans created fish ladders in areas where jumping is prohibitive; these are similar to small, water-filled steps.

Unlike Atlantic salmon (Salmosalar), Pacific salmon are semelparous, meaning that they die after spawning. But this does provide food for other species. It has been said that salmon don’t eat during their journey and die from lack of food before reaching their destination.

Fisheries, biologists and engineers have tried many methods to help salmon, but the salmon population is still decreasing.

Salmon Farms and Hatcheries

In Idaho, sockeye salmon used to travel 900 miles, and up to 6,000 feet to return to spawn. From 1985 to 2007, there was a diminishing return to the point of extinction. And once-teeming fish navigated the never-ending highway along the Columbian River Basin but now, over 400 dams with no fish ladders to pass, created a dearth. Hatcheries have become the answer and not a great one at that.

Reference

Nature. Salmon: Running the Gauntlet. Sea Studios: WNET 2011. DVD.

Catt, Thessaly. Migrating with the Salmon. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Ltd., 2011. Book.

Cooke S.J., Crossin G.T., and Hinch S.G. (2011) Pacific Salmon Migration: Completing the Cycle. In: Farrell A.P., (ed.), Encyclopedia of Fish Physiology: From Genome to Environment, volume 3, pp. 1945–1952. San Diego: Academic Press.

National Park System: Salmon Life Cycle

NOAA. “Barriers to Fish Migration”

2.0 The History of Salmon. NOAA,gov.