Pointillism and Impressionism: Learn about Artist Georges Seurat

“Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished!”

That was a harsh comment in an article, “The Exhibition of the Impressionists.” The reporter and art critic, Louis Leroy, didn’t know it at the time, but with his French linguistic agility, he had created a new word from the title of a Monet painting— “Impression: soleil levant.” Impressionism.

Not more than a year later, the term Impressionism came to represent the art, but the style itself was still not accepted into the fold of classicism. This new stage of development in art created in the early 1860s, marked the end of the classical period that had begun in the Renaissance. Georges Seurat was to take that one step further with his strange technique: Pointillism.

Suffering for Their Efforts

In the mid-1880s, the Académie des Beaux-Arts (Academy of Fine Arts) set the standard for French art in a narrow and confining manner: there were acceptable religious scenes, mythology, significant historical themes and portraits of heroes and other influential people. That’s it. It was like a straitjacket.

Not only were the themes not to be violated but the paints were somber tones using symmetrical composition and hard outlines with smooth surfaces in-between.

The Impressionist painters who had a freer style were disrespected, even shunned. Landscape paintings were branded minor, slightly inferior. The works were described as peculiar and shameful. The canvases were rejected constantly by jurors, mocked and labeled offensive for many years.

The New Movement

Claude Monet once described the Impressionist painting technique, “…try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field or whatever. Merely think, here is a little square of blue, here is an oblong of pink, here is a streak of yellow, and paint it as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it gives you your own naïve impression of the scene before you.”

Seurat’s Life

Georges-Pierre Seurat was born in 1859 in France to wealthy parents. His father, Antoine-Chrysostome was a legal official who retired early and lived in solace at the family’s second home, outside Paris. George only saw his father once a week, but grew up to be much like him, secretive and independent.

He took drawing classes at school, making close friends with artists Edmond Aman-Jean and Ernest Laurent. He was trained at the famous Ecole des Beaux-Arts and while he followed the conventional training, he was intrigued by the new wave of impressionists. He had hopes of showing at the Paris Salon, the exhibition of the best art in France.

Before La Grande Jatte

Seurat’s early drawings in Conté crayon are not mechanical, although a study called “Railway Tracks” demonstrates an industrial subject with constantly moving darks made from crayon that merge to form shadowy masses. His refined vision was astonishing for someone so young.

Seurat wanted to control colors now and studied the color theory of research scientists Eugene Chevreul, Ogden Nicholas Rood and Charles Henry. He also studied other artists such as Eugene Delacroix, who applied contrasting colors with small strokes of the brush to create vibrant, dramatic effect—he was the undisputed leader of the Romantic Movement. Delacroix served as mentor for those who attended the Barbizon School in the late 1830s, a group of like-minded artists who found fresh inspiration nestled in the picturesque forest of Fontainebleau.

Optic Mixes

Seurat found much to like in Delacroix’s painting of color opposites. This practice of dividing orange-blue, red-green into separate tints (“broken color”) produced an effect more exciting than a mixed color or a unified hue. He surmised that pigment mixtures were inferior to natural light and more luminous effects. By laying certain colors together—opposites or complementary colors—next to each other, makes both colors brighter—optical mixtures. Seen at a distance, the dots of color seem light-filled.

Seurat practiced his color theories on what he called, “croquetons” a term he invented where little panels of quick observations in paint could be carried in a slotted box, like crisp pieces of wood, akin to a cracker or biscuit. These early panels resemble works of the Barbizon School.

Two Years into La Grande Jatte

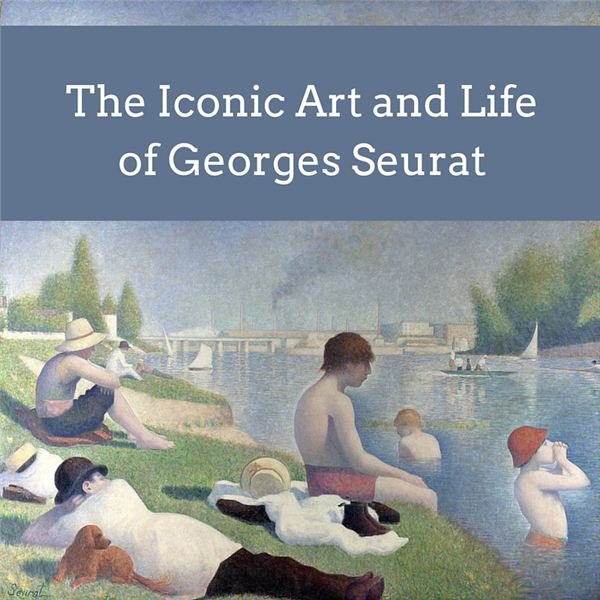

Georges Seurat’s “Un dimanche après-midi à l’Ile de la Grande Jatte” took two years to complete and didn’t show for many years until his fellow artists formed Société des Artistes Indépendants and had an exhibition in 1884. There are 48 figures, three dogs and a monkey dressed in Sunday best in Seurat’s famous painting, “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, 1884.” Even though the characters are posed (a woman is fishing, a girl is picking flowers, there is a crew rowing on the water, two military men march and a fashionable couple walks their monkey), there is life in the work.

It took over 60 studies, returning to the canvas again and again, two years of adding thousands and thousands of dots of color to create this masterpiece. It entranced and wowed viewers when it was shown in 1886 at the eighth and final Impression exhibition in Paris.

Purpose of Art

Picasso once stated, “The purpose of art is washing the dust of daily life off our souls.” Author Peggy J. Parks said it best, “…art’s true power lies not in its potential to entertain and delight but in its ability to enlighten, to reveal the truth, and by doing so to uplift the human spirit and transform the human race.”

Broadway Bound

“A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte” became the inspiration for a Broadway musical; with music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and a coordinating book by James Lapine called A Sunday in the Park with George. It was performed in many languages and many countries. We think Georges Seurat would have approved.

References

- Zaczek, Lain. Georges Seurat. New York: Gareth Stevens Publishing, 2014. Book.

- Impressionism. New York: Parkstone Press International, 2010. Book.

- Ambient Art: Impressionism. The World’s Greatest Paintings…In Your Living Room. Vat 19. Jumby bay Studio, 2004. DVD.

- Parks, Peggy J. Impressionism: Eye on Art. Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale, 2007. Book.

- Herbert, Robert L. Seurat and the Making of La Grande Jatte. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2004. Book.

- Richards, Mary. Splat! The Most Exciting Artists of All Time. London: Thames & Hudson, 2016. Book.