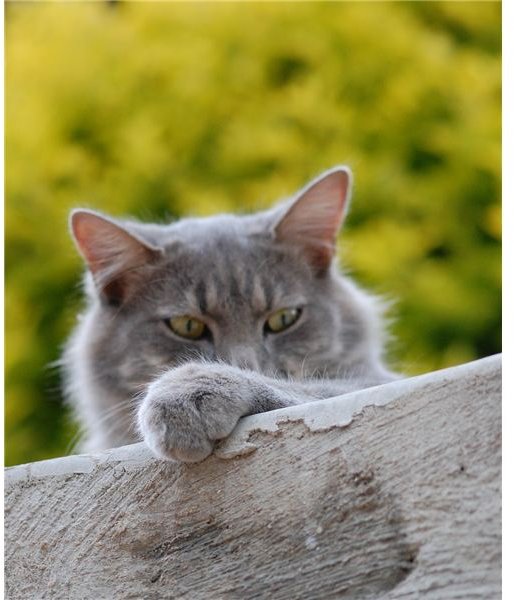

Science Homework Help: Animal Feet and Bodies - How Do Cats Land When They Fall?

Animal Physiology

This may be a new word for you, but it’s all about physiology. A Greek word, physiology means a couple of unique things. This biology study speaks to the function and activities of living things, but it is also an examination of the physical and chemical phenomena involved.

We are seeking to isolate the function of the cat in order to find out whether it’s true they always land on their feet and if yes, how is this accomplished? What is it about the cat, physically or chemically, that allows the landing to occur?

Although it doesn’t always happen and cats can suffer injuries from a fall, falling cats often do land safely on their feet.

To begin, animals have very different feet depending on whether they are large or small as feet need to be sized to carry their body weight. Their feet suit their need to either go fast or slow, travel on the ground, move in water or maneuver high in the tops of trees.

Cat Qualities

Let’s look further at cat anatomy and physiology to begin to answer our question.

For their size, cats have exceptional strength and agility. The anatomical structure of a cat shows a skeleton with many bones and some of those are similar to what a human has. There is a unique structure however, in that the cat’s collar bone is unattached to other bone structures. Therefore a cat can leap, twist and fall with grace.

In addition, cats’ muscles are striated—having parallel bundles—and the tendons are strong. This allows quick and agile take-off and the ability to continue a jump or pounce with ease because the energy to the muscles is well articulated and their “fast twitch” reflex muscles can produce a burst of high energy for rapid and powerful movement.

Cats they have soft, cushioned pads on their feet and claws coming out of their toes. On the bottom of the feet is a central pad and six separated pads (five with claws), each cushioned with fur. Those claws aid in catching surfaces and balancing.

Their ears adjust for their equilibrium giving them both mental and physical alertness and an unparalleled ability to use reflex_._

Surprise, Surprise

Veterinarians have found that cats that have fallen quite far have less broken bones than cats that fall short distances. The reasoning behind this is that cats have more time to adjust their bodies and right themselves. They can arch their bodies and put their feet under their bodies as well as under their faces using their joints as cushioning tools—bending at impact—and actually r-e-l-a-x-ing to give their extra-long vertebrae a chance to bend where and when needed. Their tails also act as a kind of rudder helping to get the position just right. (Go to Resources and follow the link to a slow-motion video of cats falling.)

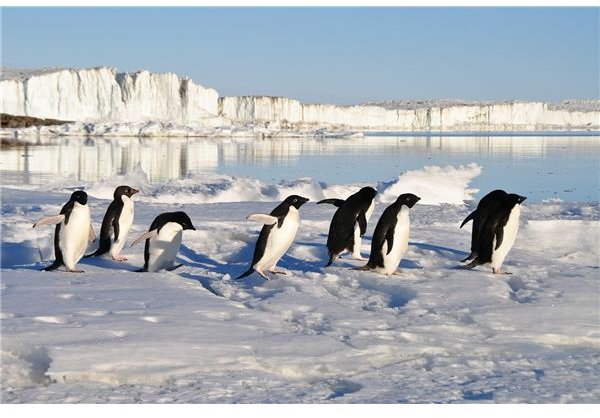

Penguins Don’t Need Slippers

Since Antarctic penguins live in constant contact with ice and snow, one would think their legs would be like frozen stumps. Not so. Again, this is due to morphology, physiology and behavior. Yes, in slipped the word morphology, meaning form and structure of anything, in this case their central body.

A penguin’s their life consists of feeding alternating with fasting for breeding and molting times when winter temps often reach 50 degrees below Celsius. Scientists tell us these experts at adaptation can shift, move and explore a new habitat, adapting to water diving and even breeding conditions quite well.

A Penguin’s Physiology

Their adaptation to cold involves their hypothalamus, nervous and hormonal systems as well as the fact that they are fat—well, they have a subcutaneous, which is a beneath-the-skin layer of fat that seeks to act as an internal insulation.

In addition, their feathers are shaped short and hide a wooly kind of down underneath. These attributes mean they can shed water faster and overlap their feathers to be sleek in the sea, cutting through the water faster. Penguins can also strut their stuff and fluff their feathers. This ability allows them some extra insulation and allows the sun to dry them faster.

We’re Very Social

Penguins make Facebook seem like child’s play because they are expert at social dynamics. They instinctively “huddle”.

Yep, they crowd together by the thousands and this is like the tightest concert you’ve ever seen. They actually coordinate their moves to get closer and move as one body into a huddling posture. Their continuous movement and jockeying for position mean the guys on the outside get moved in.

Penguins Are Controlling

Here is the miracle: penguins can control their rate of their blood flow. How? They do it by nature, and their bodies vary the diameter of their arterial blood vessels in a phenomenon called Rete Mirabile—a Latin word meaning “wonderful net.” A network of blood vessels, that is.

Under cold conditions, the flow of fluid is reduced and when warmer, the blood flow increases. This system is called countercurrent heat exchange. The arteries in their legs lead down to many much smaller vessels. Too warm? The skin and arteries dilate or become wider, bringing heat from within the body to the surface to be burned off as energy. Another group of venous vessels can bring the cold blood up from the source, such as their feet, to be warmed! Humans do this too in a modified version when their hands are white cold and turn pink when they are warm.

King and emperor penguins are able to tip up their feet too, and rest their entire weight on a tripod of the heels and tail, reducing contact with the icy surface and so reducing heat loss.

Penguin feet are actually a degree or two above freezing to the minimize heat loss and prevent frostbite.

King penguins also have mitochondrial functioning in their cells that allow them to produce heat to survive the cold without depleting their energy stores. Their body furnace is regulated to last!

Scientific Exploration

Penguins have an ability that challenges humans. They don’t suffer from many problems associated with diving, such as decompression sickness, referred to as “the bends.” They don’t get shallow water blackout or suffer free-radical damage to their tissues on the dive or return. Researchers work to understand penguins’ abilities may someday be applicable to anesthesiology and other medical purposes.

References

- NewScientist. Why don’t penguins feet freeze?. New York: Free Press, 2006. Book.

- Science Daily: The Penguin Huddle

- Kottke.org: Slow-Motion Video of a Cat Falling

- Cool Antarctica: How Penguins Survive the Cold

- Arndt, Ingo. Best Foot Forward: Exploring Feet, Flippers and Claws. New York: Holiday House, 2013. Book.

- Le Maho, Yvon, “The Emperor Penguin: A Strategy to Live and Breed in the Cold”. JSTOR: New Scientist.

- Science Daily: Understanding Emperor Penguins

- Animal Planet: Why Do Cats Land on Their Feet?