How Life Works: An Introduction to Cell Theory

Seen Any Miniature Monks?

In 1665, Robert Hooke looked through a microscope at thin slices of cork and saw what resembled the walled components that a monk would live in; he thus named these objects cells, after the monk’s room. Hooke had actually seen non-living cell walls; a live cell was not observed until 1674, by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Leeuwenhoek called the microorganisms he saw animalcules, which means “little animals”.

Once it became accepted that cells were individual units, cell theory arose. The theory stated that cells were the basic building blocks of life, that all living organisms were made up of one or more cells, and that all cells arive from pre-existing cells. Modern cell theory adds the method by which cells arrive from pre-existing cells (division), methods of energy flow within cells, and the fact that DNA is passed between cells during cell division.

Before the discovery of the cell, scientists who observed things like mold growing on food or maggots appearing in rotting meat believed that such life appears spontaneously out of inanimate material. This theory, called Spontaneous Generation, had widespread acceptance until microscropes allowed for the discovery and confirmation of cell theory.

Who’s in Command?

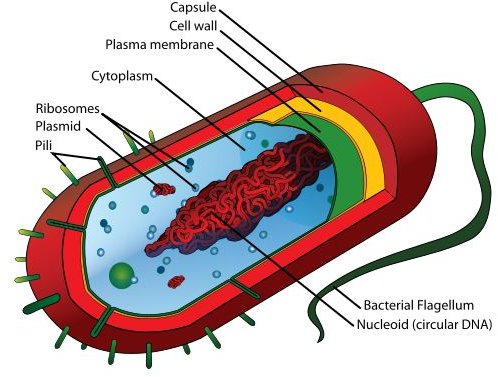

Cells come in two basic types, prokaryotes and eukaryotes. The difference between the two is that an eukaryotic cell contains a nucleus,

which carries most of the cell’s genetic information and regulates the activity of the cell. Eukaryotic cells also contain a number of smaller organelles in their membranes. For example, the mitochondria provide most of the energy for the cell, while chloroplasts (found only in plant cells) allow the cell to conduct photosynthesis.

Prokaryotic cells, on the other hand, don’t have any of that. Instead, everything in the cell is openly accessible. This doesn’t mean that the cell is homogeneous, only that the various components are not contained in discrete objects. Indeed, prokaryotic cells are very similar to the organelles found in eukaryotic cells, and can be seen as a primitive version of eukaryotes. All higher life forms are eukaryotic and most prokaryotic organisms are unicellular. A common example of a prokaryotic organism would be bacteria; a common example of an eukaryotic organism would be a human!

Reproduction, Reproduction

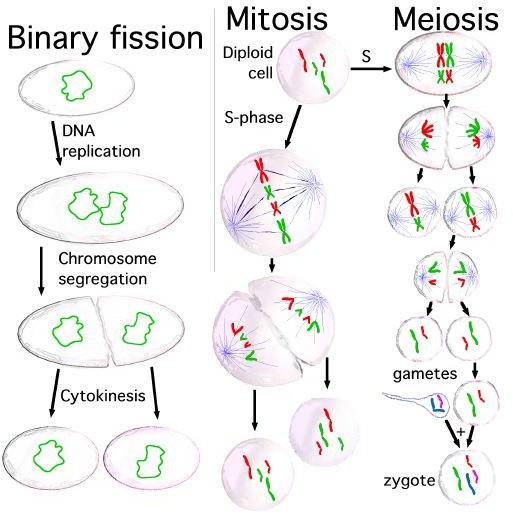

Cells generally reproduce asexually; that is, a given cell will have only one parent. While all unicellular organisms reproduce asexually, many are capable of sexual reproduction as well.

The most common method of cell reproduction is called binary fission; a parent cell simply splits into two daughter cells. Budding is similar, in that a parent cell still splits in two. In this case, however, you end up with distinct “mother” and “daughter” cells (where the mother is larger) rather than two identical daughter cells.

Sexual reproduction involves another type of cell division called meiosis, in which two cells combine their genetic material to create four daughter cells. The DNA from each parent cell is duplicated, then half of each copy is combined with half a copy of the DNA from the other parent to create the child.

In some cases, cells can undergo mutations, in which sections of the cell’s DNA are altered. This can be caused by radiation, viruses, or simply errors during the replication process. A mutation that does not harm the cell’s ability to reproduce will be passed on to its daughter cells, and can eventually affect the entire organism.

The Scientific Method

Like many scientific theories, cell theory has been developed over time by a number of people. In science, the word “theory” does not mean exactly the same thing that it does in everyday speech; rather, it is an explanation for observed phenomenon that meets basic requirements for consistency and empirical observations. In everyday speech, we may call an idea for how something might work a theory; in science, this is known as a hypothesis.

Important events in the history of cell theory include:

1665: Robert Hooke discovers the cell. He sees the cell walls of dead cork cells.

1682: Antoni Van Leewenhoek observes blood cells and describes the cell nucleus. He also invented a new method of easily creating microscope lenses, which allowed him to become the first microbiologist.

1831: Robert Brown names the nucleus; Brown also discovered cytoplasmic streaming, which is the flow of liquid through large plant cells.

1839: Theodor Schwann proposes that all living things are made entirely of cells. Schwann is also known for discovering Schwann cells, which are involved in nerve biology.

1855: Robert Remak isolates the cell membrane and describes the process of cell division. He is also known for discovering and naming the three germ layers of the early embryo.

Of course, credit must also be given to the invention of the microscope, which made it possible to study cells in the first place!

This is not an exhaustive list, as we’re still learning about the various parts of a cell and how they work together, and cell biology is an active area of research. Who knows what we will discover tomorrow?

About the Author

William Springer was formerly a middle school science teacher, a position that involved volcanos, oceans, and lots of dry ice. He recently edited an algebra textbook and is in the process of writing another textbook on theoretical computer science.

References

-

Image: Prokaryotic Cell by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal/Wikimedia Commons under the public domain.

-

Author used to be a science teacher. Names and dates were checked against the following books:

Lee, Kimberly Fekany. Cell Scientists: From Leeuwenhoek to Fuchs. Compass Point Books, 2008.

Harris, Henry. The Cells of the Body: A History of Somatic Cell Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press,1997.

-

Image: Cell Division by John Schmidt/Wikimedia Commons under GNU Free Documentation License.