Science Experiments that Show Quick Chemical Change Using Sugar

A Review of the Types of Change

Physical changes are modifications which alter an object or substance in a non-chemical manner. They change

the physical properties of the object such as size, color, texture, volume or density. For example, water transitioning from solid to liquid is a physical change. Solid, liquid, gas or plasma, it’s still good ole’ H2O.

Ripping, folding, cutting and tearing paper are also examples of physical changes. You initiate physical changes in your environment every minute of every day_. Can you think of a few?_

C****hemical change occurs inside of an object and affects its chemical properties such as toxicity, reactivity or flammability. When chemical changes occur, we’re usually able to see some sign of a reaction such as the light and sound from exploding fireworks, or the color and stench of molding bread. Unlike physical changes, chemical change cannot be undone. For example, burning wood is a chemical reaction. The process of burning releases CO2 and consumes O2. Heat and light are released. And the resulting substance, ash, cannot be turned into wood again.

Having Trouble Keeping The Two Straight?

Just ask…

- …is it reversible? (Physical changes are generally reversible. Chemical changes are not.)

- …was a new substance created? (Chemical changes produce a new substance.)

- …was energy absorbed or released? (Chemical change often takes energy. If there was a flash of light, a rise in temperature or a burst of movement a chemical reaction probably occurred.)

Read on to learn how to conduct an experiment about chemical change right in your very own kitchen.

Safety

This experiment is safe to perform in your home or classroom, as long as you take some basic precautions:

- Ask an adult. Ask an adult for permission before you start. Ask an adult for help while you are working. And ask an adult whenever you are unsure how to complete the directions in this guide. (When in doubt…ask an adult!)

- Wear safety equipment. We aren’t working with volatile chemicals here, but we will be touching some pretty hot items. So, wear a shirt with sleeves and use oven mitts or pot holders when working over the stovetop.

- Don’t fool around. This is not the time to multi-task. Don’t answer the phone or play with your dog while working. Act like the scientist that you are.

- Read all of the instructions before you begin. That way you will be prepared for what is coming next…

Warm-Up

Looking for a pre-experiment warm-up to get excited about? Here’s a 2-minute physical change that will get you buzzing. (Keep it in mind for later since it’s related to the main event.)

- Pour 1 packet of sugar into a glass of water.

- Stir until sugar is not visible.

- Sip.

The water tastes sweet, doesn’t it? This is because the sugar crystals have broken down and been distributed throughout the glass. (This is a solution!)

If you were to wait for the water to evaporate (or boil it away) you’d be left with…the sugar (or at least whatever sugar you didn’t drink!). This is because you only changed the sugar’s physical properties.

It never stopped being sugar and it always longed to return to crystal form. Once the water was gone, it was a matter of nature running its course.

Things You’ll Need:

2 Cups Sugar

1 Cup Water

1 Tablespoon Light Corn Syrup

Small or medium sauce pan (Use the heaviest pan you have)

Candy thermometer (If you don’t have one you can still perform the experiment but you will definitely need an adult to help. Read the “Up Candy Creek Without A Thermometer” section at the end of this article.)

2 Metal baking sheets

2 Sheets of parchment paper

Spoon

Note: Make sure all of your equipment is clean before you begin. Contaminants such as grease or soapy residue could ruin your experiment.

The Main Event…

1. Pour sugar, water and corn syrup into the saucepan.

2. Stir the mixture 2-5 times to spread the sugar evenly throughout the pan.

3. Place pan on stove and turn on high heat.

4. Rinse the candy thermometer under warm water for 5-10 seconds and clip it to the side of the pan so that the ball is submerged.

5. Don’t touch the pan. Do not stir the solution. Do not shake the stove. Just watch.

What’s Happening?

Now, this wouldn’t be a science experiment about chemical change without a little science. So, let’s take a minute to think about what is happening on the stovetop.

The solution of sugar, water and corn syrup is heating up–or gaining energy. And that’s a red flag for a chemical reaction about to happen.

The water reacts to the heat noticeably (physical change) and starts to evaporate–you might see some vapor leaving the pan.

A super-saturated sugar solution is left behind. (Not sure what that is? Well, picture a packed pool. There is only so much space. Eventually, you won’t be able to fit any new swimmers in the water. Super saturated solutions are substances which have no room for more molecules. If you were to add more sugar to the solution at this point, it would just sit on top.)

Remember the warm-up? Wondering why the sugar doesn’t turn back into crystals when the water is gone? Simple. The corn syrup!

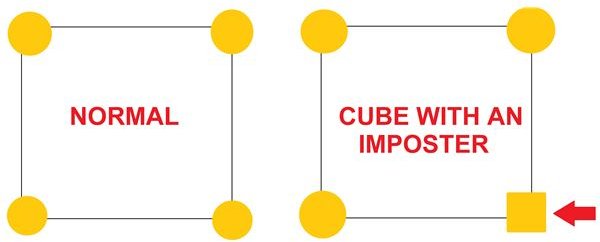

The corn syrup that is in this solution is a form of liquid sugar. When we added it to the pot, we introduced a molecular building block that was not part of the original sugar crystals. When the water evaporates and the sugar attempts to return to a solid state, the corn syrup molecules act like imposters, taking the place of certain sugar molecules. When this happens the crystal structures become unstable and the sugar is unable to return to its original form.

6. When the thermometer reads 230 degrees Fahrenheit, lower the heat to medium.

7. When the thermometer reads 300 degrees Fahrenheit, swirl the pan slowly to distribute heat evenly. (Note the change in color–a sign of chemical change. Between 320 and 330 degrees Fahrenheit the sugar breaks down into new substances–over 150 different sugars!)

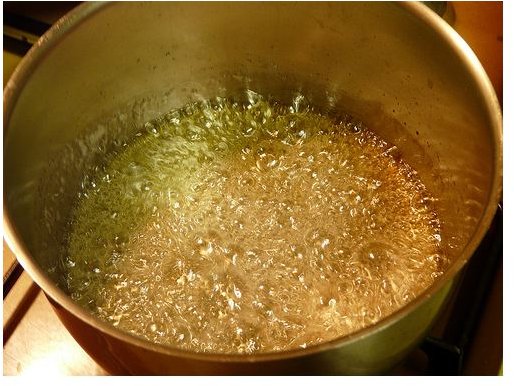

8. At this point the sugar will form mountains of bubbles. (See Picture) Wait for the mixture to turn amber, a warm brown tone. Then remove the pan from the heat. Hold the pan at a slight angle and slowly rock the mixture with the spoon.

9. Lift the spoon from the sauce pan and allow the sugar to drip back into the pot. If it drips like water, keep stirring slowly. If it falls in a smooth line, you’re ready to move on. Put the pan down on a cold burner while you prep your work area.

10. Place the cookie sheets upside down on a table or counter top. Lay the parchment paper on top of the sheets.

11. Pick up your sauce pan and place it on a pot holder near your cookie sheets. Dip the spoon into the sugar until it is coated. Lift the spoon and drizzle sugar on the parchment paper.

12. Let the sugar cool for 15-30 minutes. Then peel off and eat.

Note: If you’re feeling ambitious and have a lot of sauce left, place the pan back on the stove on medium-high heat. Let it cook until the color darkens to a deep brown. Just when smoke wisps appear on the surface of the sugar, remove it from the heat and pour 1 1/2 cups heavy cream into the pan–at arms length. Stir 2-5 times and cook over medium-high heat for 3-5 minutes.

Up Candy Creek Without A Thermometer

If you don’t have a candy thermometer, don’t feel bad. (I don’t have one either.)

You can still approximate the temperature of your candy confection using the cold water method. Here’s how it works.

WARNING: Sugar is HOT. Very, very hot. You will receive severe burns if you perform this method incorrectly. Do not underestimate the destructive power of this sweet treat; before you are able to remove the sugar from your fingertips considerable damage will be done. Only an adult or supervised teenager should perform this technique. Children may, of course, eat the cooled sample sugar!

When you cook sugar and water, it goes through several stages named after how the solution reacts when cooled in water. They are thread, pearl, soft ball, firm ball, hard ball, soft crack, hard crack and finally caramel.

For the purposes of this experiment, you only need to identify two stages: pearl (230 degrees) and hard crack (299 degrees).

Pearl is the second stage when temperature hovers between 231 and 239 degrees Fahrenheit. If you were to drizzle the heated solution into a bowl of cold water, it would form a thin thread. This thread can be molded lightly with your fingers and turned into a ball. But when removed from the water, the ball instantly flattens into a pancake.

Hard crack is the stage right before caramel. The solution is about 285-299 degrees Fahrenheit. When dropped into the water and cooled it will form a hard solid glob that can be cracked or shattered. If you can identify this stage, you know caramel is coming. Look out for a change in color. Hot caramel is a light straw color.

To conduct the cold water test:

- Place a glass bowl with cold water and 2 ice cubes near the stovetop.

- Wear pot holders.

- Dip the spoon into the solution and carefully remove 1 teaspoon of sugar.

- Drop the sugar into the bowl, directly into the water.

- Remove the pot holders and wait for at least 10 seconds.

- Gently mold the sugar with your fingers to test the texture of the solution and judge the temperature. Keep in mind that while you test the sugar, the solution is still cooking! So the pot will be hotter than your sample.

Food For Thought…

If you wet paper and it turns into pulp, have you performed a chemical or physical change?

What are the indicators that your sugar has undergone a chemical change?

Is the combination of sugar, water and corn syrup a mixture or solution? Why?

What would happen if you had stirred the solution before it was done heating up?

Enjoy Performing An Experiment About Chemical Change?

Did you have fun performing this experiment about chemical change?

Use the resources below to learn more about the science behind the sweet or hunt down some more at-home experiments.

Remember, science is better when shared–so tell your friends about your experiment and spread the joy. Or take your caramel to school and make your classmates green with envy. (Do you suppose that is a chemical or physical change?)

The Science Of The Experiment

-

FOSSweb: Mixtures and Solutions (https://www.fossweb.com/modules3-6/MixturesandSolutions/index.html)

-

Purdue: More on solubility and super-saturation (https://chemed.chem.purdue.edu/genchem/topicreview/bp/ch18/soluble.php)

-

Utah Office Of Education: 8th Grade Chemical Change (https://www.schools.utah.gov/curr/Science/sciber00/8th/matter/sciber/chemchng.htm)

-

What Is The Difference Between A Physical Change And A Chemical Change? (https://www.physlink.com/education/askexperts/ae244.cfm)

More On Sugar

- Exploratoruim: Science of Candy (https://www.exploratorium.edu/cooking/candy/sugar.html)

- Food Network: Banana Splitsville Recipe: In case you were looking for a way to use all that caramel! (https://www.foodnetwork.com/recipes/alton-brown/banana-splitsville-recipe/index.html)

The Cold Water Test

- BBC: How To Make Sweets Without Using A Thermometer (https://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A1090630)

- Exploratorium: The Cold Water Test (https://www.exploratorium.edu/cooking/candy/sugar-stages.html)

More Experiments

- Home Experiments: Nifty experiments that you can do at home (https://scifun.chem.wisc.edu/homeexpts/homeexpts.html)

- Hunkin’s Experiments: More science fun for a rainy day (https://www.hunkinsexperiments.com/themes/themes_science.htm)

Photo Credits

- “News Paper Origami Dragon Monster” by epSos.de/Flickr Creative Commons

- “Ice Drip” by PamRamsey/Flickr Creative Commons

- “Melting Caramel” by Styeb/ Flick Creative Commons

- “Sugar Cubes” by Sylvia Cini

This post is part of the series: Chemical Change for Kids

Information and experiments about chemical change for kids.