Who Was Lewis Carroll and Why Did He Write Alice in Wonderland?

He was born Charles Lutwidge Dodgson during the Victorian era in 1832, and lived a long, fairly robust and healthy life until age 66 when he died of pneumonia in 1898. As a writer he adopted the pen name, Lewis Carroll, and wrote the most fantastic and world-renown tales beginning with Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There and The Hunting of a Snark, among others. His writing life as Lewis Carroll was a dichotomy—a contradiction—of his professional life as the don of Oxford University where he taught, tutored and lectured in mathematics.

Between the Bible and Shakespeare

This young man’s writing became as world-famous and has received as many viewings as the Bible and Shakespeare. He had a knack for poetry but not just the rhyming romantic sonnets so popular then. He wrote funny, crazy and humorous tales, the kind that would delight his many brothers and sisters.

Here is a short one:

How Doth the Little Crocodile

How doth the little crocodile

Improve his shining tail,

An pour the waters of the Nile

On every golden scale!

How cheerfully he seems to grin,

How neatly spreads his claws,

And welcomes little fishes in,

With gently smiling jaws!

A Formative Family Life

Charles’s father was a clergyman, Charles was third in a family of 11 children and he grew up in a very small village in England. (There were only 143 people living in the farming community of Daresbury.)

His childhood helped to stamp his character. Charles’s father often taught his son mathematics in addition to classic and foreign languages. The family barnyard and surrounding fields and gardens provided a backdrop for made-up stories and inventing strange diversions among the snails and toads.

Railway Conductor

With so many brothers and sisters, Charles became a master at helping to raise the younger ones by creating family magazines, complete with sketches, poems and essays.

Games were a special treat of his and he invented a pastime in which his brothers and sisters pretended to be railway passengers and trains. He constructed a miniature replica out of a wheelbarrow, a barrel and a small truck. Passengers had to buy tickets and follow a timetable. Each station had refreshments. If a passenger fell off a train, they had to be run over three times before they could ask for a doctor and those who behaved badly went to prison.

With such a creative, captive family for an audience, Charles also entertained himself and the others by performing magic tricks and putting together marionette shows. However, life in the Dodgson household also meant following a strict regimen. All the children learned religious rituals, Christian responsibilities such as reading the Bible and memorization of prayers.

His mother was very beloved and educated her daughters at home as was the convention of the times. Her children said that never in all their lives did she utter an impatient or harsh Word, and she often said that she “had not a wish unfulfilled.” As Charles was the eldest son, he helped to nurture the others and his mother made him her special pet as she knew of his uncommon nature.

School Star Pupil

In 1846, he entered Rugby School and in 1854, he graduated from Christ Church College, Oxford. With a keen aptitude in mathematics and writing, he remained at the college after graduation to teach. A fellowship allowed him to live there for the rest of his life. His mathematical writings included An Elementary Treatise on Determinants (1867), Euclid and His Modern Rivals (1879) and Curiosa Mathematica (1888). While teaching, Carroll was ordained as a deacon; however, he never really preached.

He tutored for a long while and often complained about the entry standards for the college and his students’ lack of skill and poor attitude toward mathematics in general, although he was respected for his unselfish habits and valued as a tutor and friend as he often tried to make learning fun with secret skills and illustrations.

Through a Lens

Dodgson was a keen amateur photographer—a pioneer really—with a particular interest in photographing little girls, whose friendship he valued highly. He also took many photographic portraits of poet Alfred Lord Tennyson’s sons.

His favorite subjects were the daughters of the Dean at Christ’s Church, Henry George Liddell (often referred to as H.G. and Liddell rhymes with “middle”). A man of considerable reputation, Liddell’s thirty-six year reign at Christ Church is amply recorded. Charles and the dean were on good professional footing and after gaining all his photographic apparatus, Charles’ other occupation became taking photos of Liddell’s daughters: Lorina, Alice and Edith, and that made Charles a frequent visitor at the “Deanery.”

Charles had a stutter. While he was always polite to grownups, because of his speech impediment, he preferred the relationships with children versus adults. Nevertheless, talk has always swirled around his preference as being fixated on children.

The Real Alice (Liddell)

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland originated on a boat trip with the young daughters of Liddell (although others reported it resulted from many previous installments that grew and changed over time). Actually, the first Alice’s adventures were “Underground.” Later, after much expansion and more careful deliberation, the location turned into Wonderland.

The “golden afternoon” on the river in 1862 saw Charles in his element with the three Liddell sisters—ranging in age from eight to thirteen—and his friend Robinson Duckworth, gliding languidly over shimmering water. Everyone in the boat was looking forward to the ride and picnic. “Tell us a story” was the prompt and it poured out, the story of Alice down the rabbit hole.

The next day, Alice pestered him—actually more than once—to write the story down for her and the rest they say, is history. He made a copy by hand with his own illustrations and gave it to Alice. Publication followed.

One reviewer attributed the success of these works to the fact that, unlike most children’s book of the era, they had no moral and did not explain anything. Most books of that period were written to teach children how to behave, to obey rules and to do as they were told.

The sequel to the book, Through the Looking-Glass was published in 1871.

References

- Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland movie, McLeod, Norman Z., 1898-1964. [United States]: Paramount Pictures : Made available through hoopla, 1933. 1 online resource video file (ca. 77 min.): sd., col.

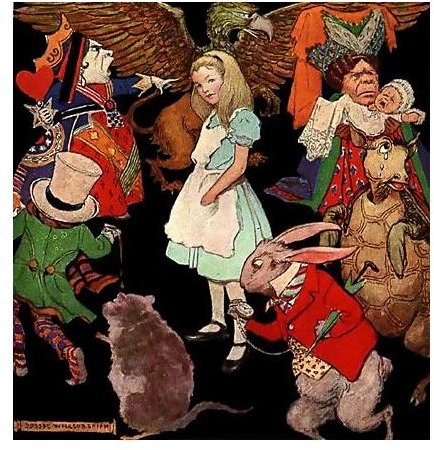

- Image Source: “Alice in Wonderland”. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Drabble, Margaret, Ed. The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. Book

- Lewis Carroll Society of North America

- Cohen, Morton N. Lewis Carroll: A Biography. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. Book.

- Mendelson, Edward, Ed. Poetry for Young People: Lewis Carroll. New York: Sterling Publishing Co.,2000. Book