Issues That Bring About Teacher Strikes: More Than Just the Money

The Emotional Investment

The strike in Chicago in 2012 stirred up a lot of emotions across the entire country. When private sector workers strike, it’s not uncommon for us to “pick a side” and voice our support for either labor or management. But unless we’re closely connected to the particular dispute at hand, most of us will just watch the situation with interest without getting too emotionally involved.

However, when public employees go on strike, our reaction is usually quite different. The issues surrounding the strike tend to hit a lot closer to home, and frustration is felt by a much larger base. The effects of the disruption are often more widespread – and even when we’re not personally affected, we can easily empathize with those who are. Plus, whether we support the workers or not, we still have to find a way to deal with the fact that the services they supply have been suspended.

When Teachers Strike

When teachers take up spots on a picket line, tensions can rise to a whole new level. After all, even if it’s been a while since we’ve been in school ourselves, most of us still know people who are teachers or who have kids in local public schools.

Kathy Horn, a marketing professional from North Carolina who now has a 21-year-old son of her own, still remembers her own experience as a student during a teaching strike. “Our teachers went on strike at the beginning of my junior year of high school in Pennsylvania in the late 1970s. The schools were closed a little over two weeks. Those two-plus weeks were added to the end of the school year, pushing into the heat of summer (with no air conditioning, I might add!). Unfortunately, the teachers taught and gave final exams based on the original schedule. This meant that those make-up days were spent sitting quietly in the classroom either reading or watching movies. While I had no issue then with the strike (and understand bargaining issues even more clearly now), I am still upset all these years later that two weeks of my time was wasted. The students should not have been penalized due to the dispute.”

Matters related to Horn’s last point were brought up quite a bit during the Chicago strike. Opponents of the strike questioned the teachers’ dedication, claiming that if they cared so much about their students, why weren’t they in the classroom teaching them? Those who supported the strike replied that the teachers were fighting for things that would greatly improve the quality of their students’ education and against other things that would make the current situation worse.[1] But, even in that latter group, many if not all were hoping for a swift compromise so that both teachers and students could head back to school as soon as possible.

Looking For Someone to Blame

A 2012 Gallup poll found that only 37% of Americans believe that our nation’s public schools provide children with an excellent or good education – independent private schools received an excellent or good rating 78% of the time, and charter schools were given these same high marks by 60% of those surveyed. Since our overall perception (whether that perception is right or wrong) of our public school system isn’t that great, it’s only natural for people to ask what’s being done to fix the problem.

These questions are generally directed toward those we consider to be officials and leaders – school board members, administrators, politicians and so forth. In response, they usually talk about plans to implement more rigorous standards and to hold teachers more accountable for student performance. Unfairly or not, many are interpreting these remarks to say “bad teachers” are to blame.

Dr. Jennifer Little of ParentsTeachKids.com has over four decades of experience working with learning-challenged students and is all too familiar with the political issues faced by teachers. “Teachers are angry. They’ve had to stand there and take it from administrators, the public and the media. They’re tired of being offered up as sacrificial lambs.”

Little continues, “Educators are being held accountable for things that they’re not allowed to do. By this I mean they are not allowed to do the remedial instruction they know is necessary, because they have to teach the standards regardless of whether or not the students have mastered the prerequisite skills.”

In addition to being pushed into the spotlight as the ones to blame, teachers are increasingly receiving more and more top-down mandates without being having a chance to voice their frustrations or their own ideas on education reform. So, what’s left to do?

Turning to the Bargaining Table

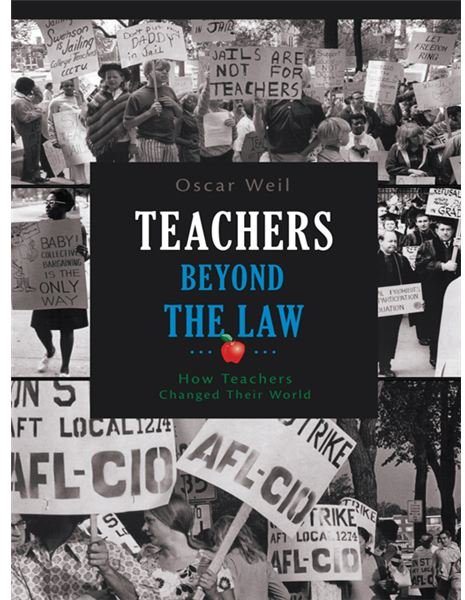

Oscar Weil, former executive director of the Illinois Federation of Teachers and author of the book <em>Teachers Beyond the Law: How Teachers Changed Their World</em>, points out, “Bargaining gives teachers a chance to communicate with the public, otherwise their voices aren’t heard. It also gives them the opportunity to negotiate in public. School boards and administrators are reluctant to do that, because they don’t want any dirty laundry unfurled in front of voters.”

In the Chicago strike – and in other collective bargaining situations that have taken place over the last several decades – many teachers and union leaders have claimed that money isn’t the main issue. Instead, they point to issues such as “…disruptive school closures, disregard of teachers’ and parents’ input, testing that squeezes out teaching, and cuts to the arts, physical education and libraries…”[1] This argument doesn’t always sit well with the general public and often leads to another question.

If It’s Not About the Money, Why Ask for Higher Wages?

Although there are federal laws that protect and support the rights of private sector workers to join unions and participate in collective bargaining, public employee rights are determined on the state level. Even if a state does grant bargaining rights to public employees, it can place limits on what types of issues are allowed to be negotiated. For instance, Section 4 of the Illinois Public Labor Relations Act states:

“Employers shall not be required to bargain over matters of inherent managerial policy, which shall include such areas of discretion or policy as the functions of the employer, standards of services, its overall budget, the organizational structure and selection of new employees, examination techniques and direction of employees. Employers, however, shall be required to bargain collectively with regard to policy matters directly affecting wages, hours and terms and conditions of employment as well as the impact thereon upon request by employee representatives.”[3]

To put things in plainer terms, if teachers’ unions want to make sure that collective bargaining efforts meet legal guidelines in Illinois, compensation should be a central issue. Then, they can figure out how other grievances relate. Or, as Phil Cantor told Amy Goodman in a <em>Democracy Now!</em> interview, “We’re not allowed legally to strike over anything but compensation. But teachers are not most interested in compensation; we’re most interested in being able to do our jobs for the students we serve. So, you know, I think we’re trying to tie other issues that we feel are very important to compensation, so they’re part of the bargaining table agreement.”[5]

Future of Education Reform

One thing that the Chicago teachers strike made abundantly clear is that, when it comes to matters related to education reform, there is a definite division of thought. That point alone should be a wake-up call to everyone involved. If any reform effort is going to truly succeed, it’s going to need significant buy-in from all parties – especially parents and teachers.

So, if the education reform efforts currently being put forth by federal, state and local governments aren’t a step in the right direction, where do we go from here?

Weil makes an excellent observation, “Instead of talking about how to get rid of bad teachers, we should be more focused on what we need to do to get good teachers. Many of the best teachers don’t want their kids to be teachers. They don’t want them to deal with the same frustrations they do.”

But is it even possible to stop playing the blame game and instead start working together to build better public schools that nurture the educational needs of all children, including those from low-income families? Let’s hope so. As Little reminds us, “School is the only hope for kids living in poverty, because without skills, that will be their life’s path.”

References

-

[4] “In U.S., Private Schools Get Top Marks for Educating Children.” Gallup. Published August 29, 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2012 from http://www.gallup.com/poll/156974/private-schools-top-marks-educating-children.aspx.

-

[1] Karen Lewis and Randi Weingarten. “A Gold Star for the Chicago Teachers Strike_.” Wall Street Journal_. Published September 23, 2012. Retrieved on September 25, 2012 from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444032404578010731103676940.html

-

Image Credits:

Chicago Teacher’s Strike by Brad Perkins under CC BY-SA 2.0

-

[3] “Illinois Public Labor Relations Act.” Illinois General Assembly. Retrieved on September 25, 2012 from http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/ilcs3.asp?ActID=108&ChapterID=2.

-

[2] “National Labor Relations Act.” National Labor Relations Board. Retrieved on September 25, 2012 from https://www.nlrb.gov/national-labor-relations-act.

-

[5] “Striking Teachers, Parents Join Forces to Oppose Corporate Education Model in Chicago.” Democracy Now! Published on September 10, 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2012 from http://www.democracynow.org/2012/9/10/striking_teachers_parents_join_forces_to.